I’ve been wondering for quite a while whether I should keep my Flickr account or not. One of the reasons why I didn’t close it yet, is because going on Flickr and seeing what others were doing made me feel I had to work harder in order to improve.

Slowly this feeling vanished. Nonetheless, I thought it was an opportunity to compare my work with the work of other photographers. Then I realized there’s no reason to have a Flickr account. I can look at those galleries without necessarily having one. Or better yet, go to a real gallery and see actual printed photos. For what concerns having my work in a social media gallery, there isn’t much reason either. What would be the point? Let’s do a quick analysis.

Two good things about social media which aren’t so good.

- Followers. There are techniques to gather a growing multitude of followers. The morality of such methods is simply questionable. In fact, understanding those behaviors made me question the sense of a Flickr account in the first place or any other social media.1

- Gratification. How nice it is when we get that comment, or we see our Likes counter increasing! Well, assuming we didn’t go the dirty technique route (which I will explain later), and we’re playing a clean game, then we shouldn’t feel bad for some appraisal. After all, we worked for it! The thing is, a comment like “Nice capture” doesn’t help us get any better. It may only help our self-esteem, and if that’s the case, it means it is not photography that we need in order to feel better, but some evaluation of what we are as human beings. In other words, I believe that whenever people look for an “Awesome work!” comment, their main aim is not the work itself, but something personal that goes beyond the nature of the job they’re doing.

But why do we never get a comment about the composition, the light, or what we could do in order to improve the photograph? Two reasons: people are not interested and people don’t know. Well, there’s also a third reason: time. With everything we go through every day, it’s difficult to give some random dude serious feedback. And that’s the problem with social media. And to be clear, this is not the case of “there’s nothing wrong with it, it is how we use it that makes the difference”.

Some things are built wrong.

General David Sarnoff made this statement: “We are too prone to make technological instruments the scapegoats for the sins of those who wield them.

The products of modern science are not in themselves good or bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.” That is the voice of the current somnambulism. Suppose we were to say, “Apple pie is in itself neither good nor bad; it is the way it is used that determines its value.”

Or, “The smallpox virus is in itself neither good nor bad; it is the way it is used that determines its value.” Again, “Firearms are in themselves neither good nor bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.” That is, if the slugs reach the right people firearms are good.

If the TV tube fires the right ammunition at the right people it is good. I am not being perverse. There is simply nothing in the Sarnoff statement that will bear scrutiny, for it ignores the nature of the medium.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media

So, what is wrong with social media? Let’s consider the popular Facebook. Hundreds of posts every day, many of which are irrelevant. There’s some brief conversation, which usually involves a few “likes”, perhaps a link or two to some website. This is the average scenario. Facebook has not been created in order to give people a proper tool to communicate. It is a platform where we can experience little samples of Warhol’s 15 Minutes of fame phenomenon, but it is not meant for any serious exchange.

It is also permeated by a narcissistic attitude, although it is a deceiving idea of narcissism. Of course, we do like feeling appraised, but it is not just that. McLuhan has a better explanation of narcissism. For him, it is what we perceive as an extension: not being able to recognize the image reflected, there’s a deceptive perception of the other than the self, which eventually will anesthetize our perception.

The youth Narcissus mistook his own reflection in the water for another person. This extension of himself by mirror numbed his perceptions until he became the servomechanism of his own extended or repeated image. The nymph Echo tried to win his love with fragments of his own speech, but in vain. He was numb. He had adapted to his extension of himself and had become a closed system.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media

A large part of the tools we use nowadays, especially the most appealing ones (technological tools, electronic devices, social media, and so on), fall into McLuhan’s narcissistic interpretation. The tools we use have become extensions. We can’t disconnect, we experience them in a sort of endless loop. A closed system as McLuhan describes it, in which the input and the output overlap, and what could be expressed with one’s own sentences and words, becomes a link to a website, a quote, an image, or a photograph.

Since the tool is our extension, hence the idea that a professional tool makes us professionals. We all, at some point, saw someone with a big, expensive camera and thought, even if for a moment, “he must be a professional”.

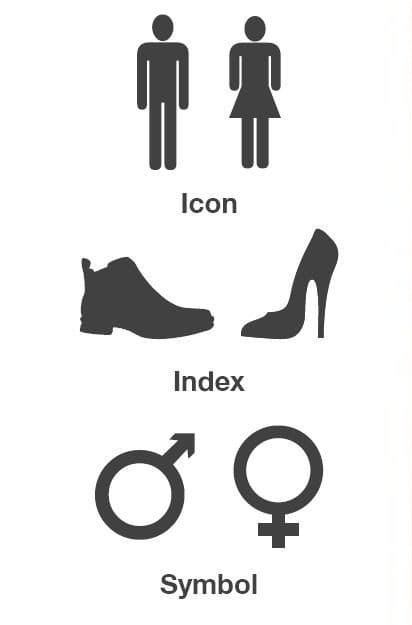

We experience signs, not symbols.

The need to speak, even if one has nothing to say, becomes more pressing when one has nothing to say, just as the will to live becomes more urgent when life has lost its meaning.

Jean Baudrillard, The Ecstasy of Communication

Considering today a significant part of our communication is experienced through the use of images, the quote above is pertinent to photography as well, thus “nothing to say” sounds particularly appropriate to look at the plethora of images produced every day. How many accounts on Instagram, Flickr, 500px, and so forth, are really needed? Let’s rephrase it: how many of those accounts really add something significant to photography?

Now, of course, we can’t evaluate all those galleries from a quasi-elitist standpoint. A lot of them simply fall into the category of people who do it for fun. After all, life requires some amusement. The thing is, there is no difference between a gallery by a truly passionate and one by somebody who has no particular interest in photography per se, but rather in the social experience that the network fosters. Social media really is a leveler. What really matters are the numbers, and those numbers have little or no relation to the quality of the gallery itself or the content.

Where it gets really dangerous is when we realize that the quality itself really doesn’t have much relevance anymore, because the very signified is being exhausted by the signifier.

Information devours its own content. […]

Rather than creating communication, it exhausts itself in the act of staging communication. Rather than producing meaning, it exhausts itself in the staging of meaning.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

In other words, what really matters is the means itself rather than the outcome. Whatever the meaning may be, it is the signifier that now takes over. It is not what we read or see on Facebook, it is the very experience of Facebook that in the end overshadows its own content. It is not the gallery on Flickr with our work and hours spent producing it that really matters, it is the number of followers, favorites, and comments that come into play here. Also, notice what happens to your pictures when you post them on Instagram: they suddenly look different. They have to adapt to a format, and that format is what gives them a new identity, almost as if those pictures were taken by someone else.

The symbolic power of the work of art has surrendered to the subduing speed of the sign. What we experience on any social media ceases to have any meaning and becomes a strand that is part of the flow that travels faster than any form of media we have experienced thus far in our entire history. Ever wondered why so many copycats nowadays? And yet, rip-off is not even an issue anymore. If a sign is floating on the Internet, then it is practically available to anyone. Mantras such as “steal like an artist” are all over. There’s no copy anymore, and there’s only the illusion of reality. The output and the input are now part of a closed circuit, whatever goes out, comes back. There is no source, as the user is the source and the destination at the same time.

By crossing into a space whose curvature is no longer that of the real, nor that of truth, the era of simulation is inaugurated by a liquidation of all referentials – worse: with their artificial resurrection in the systems of signs, a material more malleable than meaning, in that it lends itself to all systems of equivalences, to all binary oppositions, to all combinatory algebra.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

The sign is indeed more malleable than meaning. Being the sign less abstract (the name is the thing; the swoosh is the shoe; the flag is the nation; money is power; and so on), being a closed circuit, it is paradoxically more open than the meaning as we can virtually use anything since there is no need to expand on the absence of a concept.

The system we experience has, ultimately, become self-referential. We, the so-called “content creators”, are at the same time producers and consumers. In this unprecedented continuous overflow of signs which along their paths have to cross no boundaries, it has become indiscernible where they originated from and where they are headed to. It is a liquid network, where no boundaries exist as well as no differences either.

We believe that having a faster way to communicate at our disposal also triggers a more creative environment. I don’t agree with that. More often than not, I find that disconnecting and being by myself is the only way to cleanse my mind from all the so-called references, which I believe have just become repeating patterns rather than inspirations.

How to increase your followers.

So, what about the techniques I mentioned earlier?

They are very basic, and they work. Let’s take the case of a Flickr account (but it may well apply to other social media).

First, you need to start following people, the more users you follow the better. Then you want to start picking your favorites, loads of favorites. Now you start slowly posting your own images and, as you do that, you won’t stop doing the first and second steps. And now comes the best part (you might not need this). Among the steps mentioned here, this is the most embarrassing one: you now have a good amount of followers, and you want to keep growing your audience, so you keep adding other users, with a difference, though. Check if they started following you as well, if not then unfollow them. Basically, what other people’s galleries look like has no importance, because once you have gained enough followers, they are just numbers. Hence, if they follow you, they are worth it, otherwise, don’t give them anything for free.2

The outcome.

Is photography dead?

Since photography is subject to the culture that produces it, experiences it, and uses it, to give a proper answer we need to look at the context where it is employed. The nature of the Internet, and more specifically of social media, works as a filter that turns virtually anything into its own byproduct. It makes more sense to ask: has social media changed the way we experience photography? Definitely, and it’s been a drastic change to a point of no return. From this standpoint, photography is dead, although it is insofar as we keep experiencing it the way we currently do.

The way social media works doesn’t allow the luxury of any suspension. There’s a massive loss of meaning, a staged illusion that took its place. So how can photography outlast?

Despite photography by nature being a fast means of production, on the other hand, the complete assimilation of a photograph as a work of art would presume the very suspension that we seem to lack nowadays. Experiencing photography as we do these days undermines its very nature.

I have personally lost any optimism about the social media idea. I deleted my Facebook account already 6 years ago, and I keep a Tumblr account only as a repository for things I find around that I consider interesting, or stuff that might be useful for my work.

The two accounts left are Flickr and LinkedIn, and I’m seriously considering closing the former.

- For those who use social media in order to increase their connections and their visibility for work opportunities, I understand that followers can make a difference. That said, in those cases, shady methods aren’t less deceptive, and I don’t personally consider them less questionable. ↩︎

- I’m sure there is more other than these few basic steps, like services people pay for, robots, and so on, but I think the steps above hold true for the majority of the cases. A few take some steps further, and apparently, they make a living out of it, and I can see why they get serious about their social profile. Then again, the purpose of their work is their profile, not photography. The latter is only a means. ↩︎

Leave a Reply